In June 2018, the commission on Fake News and the Teaching of Critical Literary Skills in School reported that only 2% of young people in the UK “have the critical literacy skills they need to tell if a news story is real or fake.”

The study also learned that 50% of UK teachers felt that “the national curriculum does not equip children with the literacy skills they need to identify fake news.” A third believed, “the critical literacy skills taught in schools are not transferable to the real world.”

And the UK isn’t alone.

In November 2016, the Stanford Graduate School of Education reported that the majority of US students struggle with information literacy, and are unable to distinguish between credible and unreliable news articles.

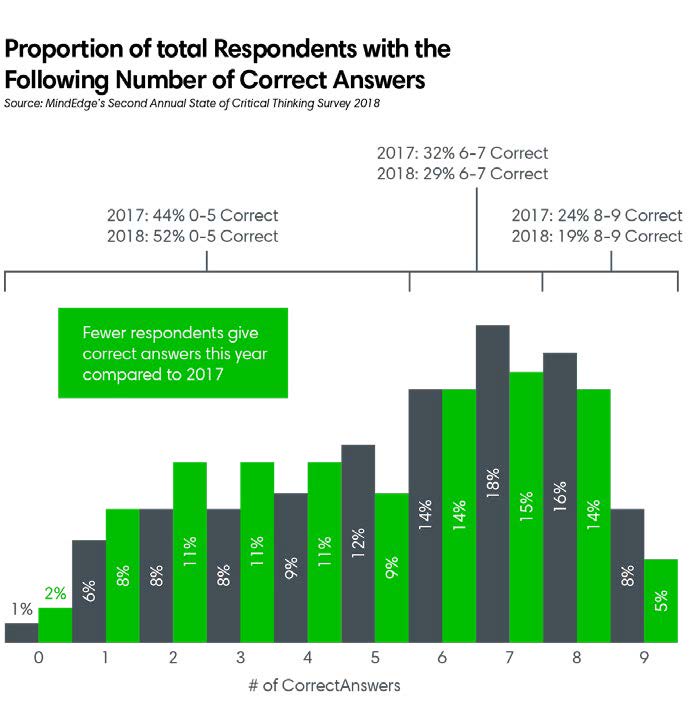

Last year, the State of Critical Thinking study from MindEdge found that although young college students and recent graduates were confident in their critical thinking skills, in actual fact their ability to detect fake news online is declining.

Information literacy, or the lack thereof, is a global concern.

Information literacy, or the lack thereof, is a global concern.

What is information literacy and why is it important?

According to the Association of College and Research Libraries, information literacy is:

“the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.”

Information literacy empowers people to learn for themselves so that they can make more informed decisions. It helps them recognize biases, understand context, and evaluate information so they can effectively use and communicate it. It’s a lifelong skillset that meaningfully impacts every person’s education, career, civic engagement, and personal life.

We’re drowning in a firehose of data

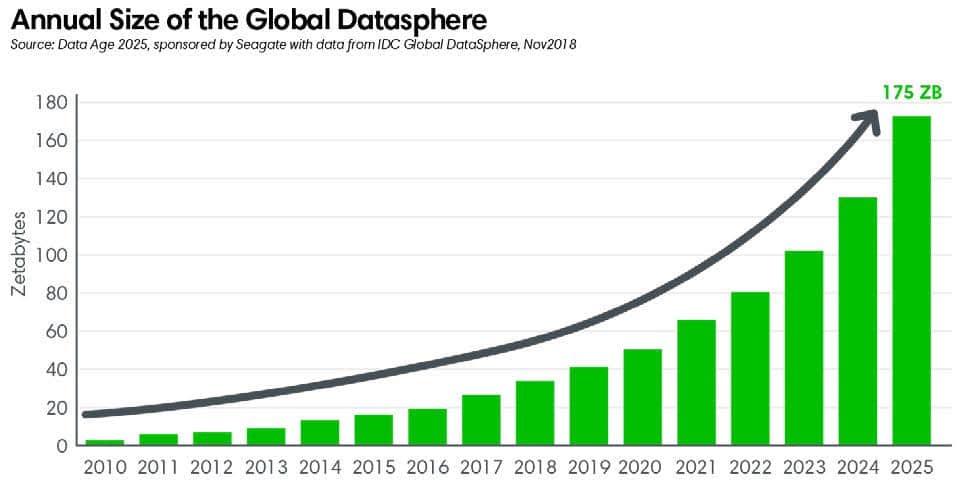

According to IDC, there was over 20 ZB of data on the internet (~22 trillion GB) in 2018. That equates to more than 60 billion GB of content being created every single day! Even more astounding: 90% of all that online data was created in just the last two years.

IDC predicts that by 2025 the global data sphere will be 175 ZB.

What does this mean? Well, now almost four billion people are drowning in information, but still starving for quality, trusted content.

Today’s news never sleeps

The pervasive 24-hour content cycle may seem like a dream come true for news junkies, but for most people it’s a nightmare. Driven by the desire for more eyeballs and speed, publishers’ continual recycling of stories with only minor updates is actually hurting us – distorting our perceptions of reality with over-sensationalized ‘breaking news’ that isn’t really news at all.

“The nasty little truth about 24-hour news – whether cable TV or the Internet – is that most of it is not news. Looks like news. Sounds like news. Smells like news. But nope, it isn’t news.”

Howard Rosenberg, Charles S. Feldman, Co-authors

No Time to Think: The Menace of Media Speed and the 24-hour News Cycle

There’s never enough time for people to analyze any of it – meaning no time for proper critiquing or fact-checking. Media websites that are constantly being updated have become nothing more than a snacking tool, and a dangerous one at that.

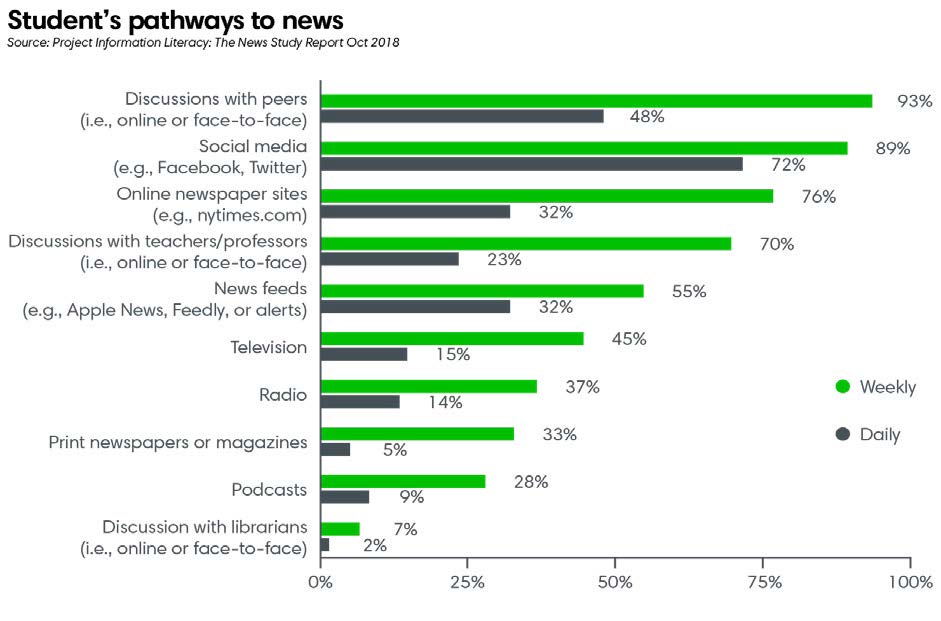

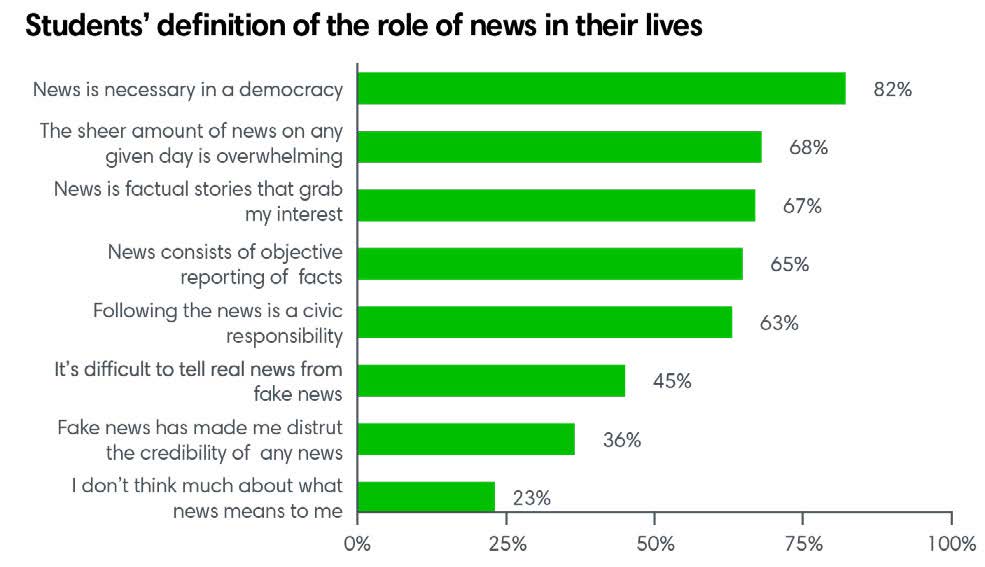

In a recent Project Information Literacy (PIL) News Study Report, 68% of students surveyed said the amount of news available to them was overwhelming, with 51% saying it was difficult to recognize the most important news stories on any given day. And the intrusive nature of the news that finds them (even when they’re not looking for it) was frustrating for the majority.

“News interrupts my life a lot, especially when I’m on Facebook and I’m looking at friends’ pictures and enjoying myself and then there’s videos about violence in Gaza and I think, “Oh God, I can’t avoid news!”

Female student

Life and Physical Sciences major

PIL study

Who can we trust?

Early in 2019, Mike Caulfield, director of blended and networked learning at Washington State University Vancouver, and head of the Digital Polarization Initiative of the American Democracy Project, wrote a compelling article about the scarcity of attention. He insists that in our so-called ‘information age,’ content is becoming less and less valuable as it becomes more and more commodified.

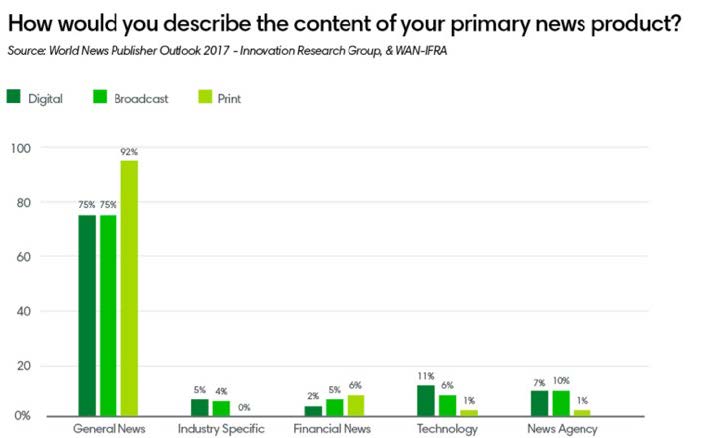

It’s hard to argue with Caulfield when you look at the WAN-IFRA 2017 Outlook report, and see that the majority of media organizations are just regurgitating over-published general news content from wire services.

As a result of this commodifying of content, a student’s primary skill becomes their ability to make quick decisions about where best to focus their eyes and ears in a world where dubious outlets are vying to capture their attention and influence their beliefs, decisions, and behaviors.

In our attention-scarce world, Caulfield argues that everything is suspect – an assertion supported by the PIL study. 72% of those surveyed said that “without knowing the source of the news — where a news item originated — they could not trust a news item.”

“What I find with many students is they are trust misers — they don’t want to spend their trust anywhere, and they think many things are equally untrustworthy. And somehow they have been trained to think this makes them smarter than the average bear.”

Director of blended and networked learning

Washington State University Vancouver

So, who’s trained them? It doesn’t appear to be those in academia, given the lack of attention information literacy is getting in many school curriculums.

According to PIL, only two out of the 18 institutions in their study had a full-term information literacy course requirement for all students to graduate. When it comes to students’ pathways to legitimate news, librarians are sadly underutilized. Students don’t know what they’re missing.

However, although students discover most of their news through friends and social media, and despite being overwhelmed by its sheer volume, they do recognize the importance of news in their lives.

They appreciate news’ value; they just need help finding the fact-based, trusted content that will serve them best in their studies and their lives.

Journalism today

Few would argue that since the advent of the internet, journalism’s challenges have been daunting. On almost a daily basis we read about how news professionals all over the world face:

- Demands to do more with less

- Increased competition from social media, bloggers, and digital-only media

- Pressures to be first rather than be factual

- Massive layoffs

But despite all this, the core principles of journalism – accuracy, truth, impartiality, fairness, humanity, and accountability – still remain. And they resonate with people, including our youth.

74% of students in the PIL study said that they trusted professional journalists from traditional outlets more than social media sites that allowed anyone to post news. And many students automatically conferred authority and assigned trust to well-known sources like The Washington Post and The New York Times.

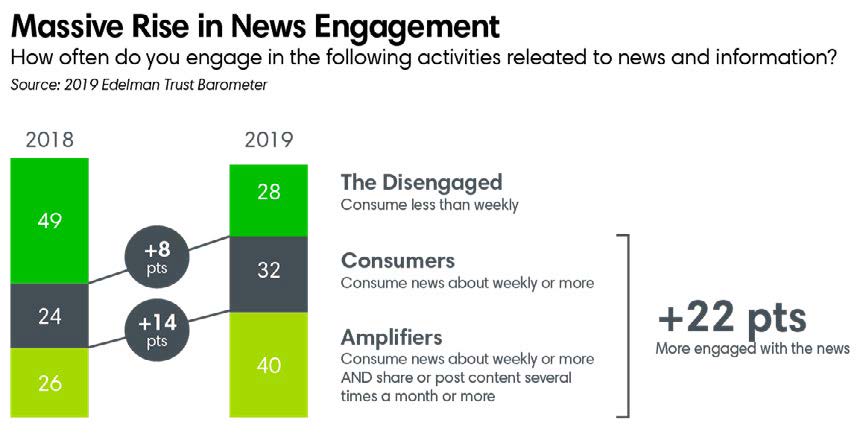

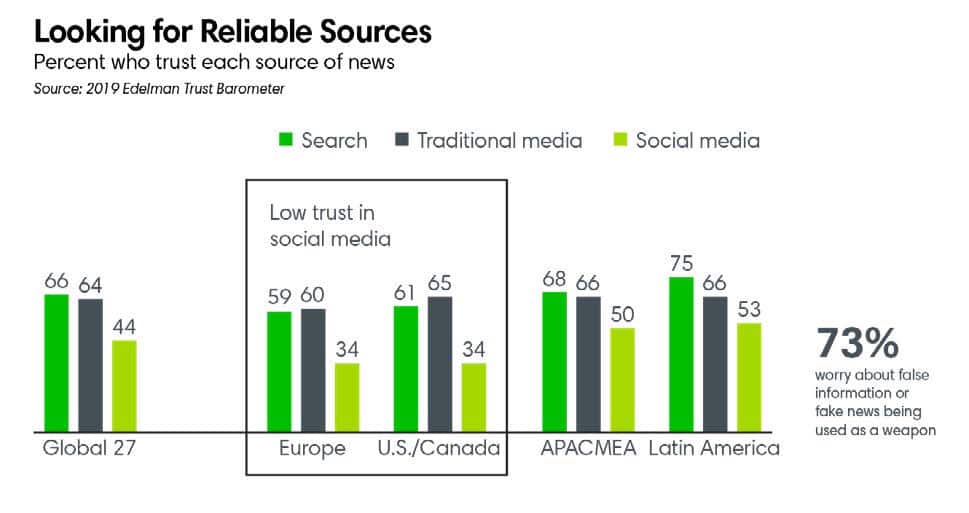

The war against fake news and propaganda isn’t over, but there are signs that trust is moving in the right direction. According to Edelman’s 2019 Trust Barometer, traditional news media engagement rose by 22% in the past year, with traditional publishers now the most-trusted sources, particularly in North America and Europe.

And as people seek out more reliable sources, traditional journalism bears a hallmark of trust.

The future of digital news access is uncertain

Back in 2015, the European Union put forth the Digital Single Market Strategy proposal which included a highly contested Directive on Copyright in the EU. The Directive includes a range of initiatives to “modernize copyright rules to fit for the digital age.”

Two of these directives are expected to have significant implications on digital news and students’ access to quality media.

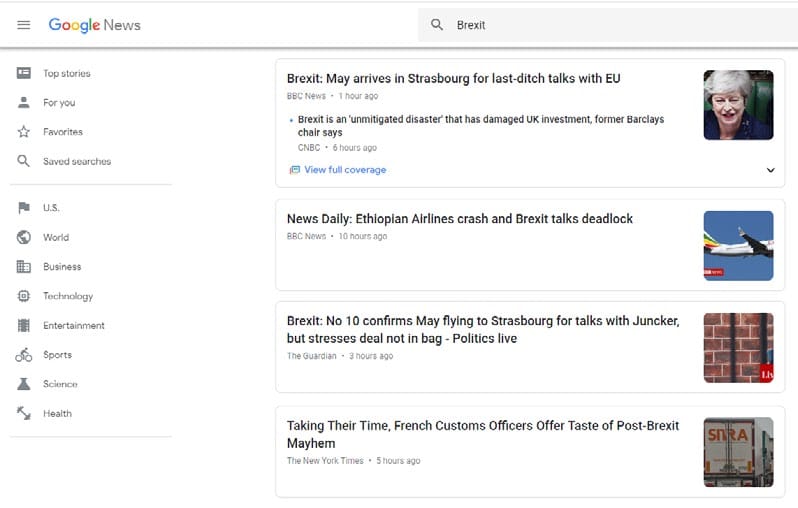

Under Article 15, news aggregators such as Google News will only be able to share “very short” snippets of text on their newsfeeds, compared to the larger snippets (as shown below) that we’re used to seeing – snippets students often use to determine whether a story is worthy of deeper scrutiny.

Publishers contend that displaying these larger snippets infringes on their copyright, believing it gives them renewed powers to speak to the googles of the world and demand fair compensation.

News aggregators argue that they shouldn’t have to pay for the snippets, because they make publishers’ content more discoverable and drive traffic to their websites, at no cost.

It’s an ongoing battle that could result in Google, Yahoo news, and others significantly curtailing the amount of content made available to readers.

“Google News might quit the continent in response to the directive. The internet company has various options, and a decision to pull out would be based on a close reading of the rules and taken reluctantly.”

Jennifer Bernal

Public policy manager for Europe, the Middle East and Africa

I hope this isn’t the case and that both sides will come to an agreement on what a fair compensation model should look like.

Article 17 requires platforms that support user generated, or shared, content (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube) to “monitor and proactively screen content uploads for potential copyright infringement or face liability.”

Many critics claim that Article 13 will actually consolidate power among the major tech companies (not weaken it), restrict freedom of expression, and potentially lead to censorship that could harm smaller content producers.

Article 13 could also encourage platforms to cherry pick content to save money – a practice that could result in even deeper echo chambers, more native advertising posing as editorial, and increased bias blindness thanks to reduced exposure to multiple perspectives on news.

The text for the legislation around these two Articles was finalized in February 2019, and once ratified, member states of the EU will have two years to implement it.

Implications for students

If one accepts publishers’ general assertion that someone needs to pay for content production – whether that be readers, news aggregators, or social platforms – then publishers need to reinvest digital revenue in creating higher quality content.

But if content discovery is curtailed by major tech platforms, how can publishers hope to create trust with readers? How can they demonstrate their value such that people decide they want to pay for a subscription? How can students, who often can’t afford to pay much for content, determine whether a “very small snippet” of content is worth their time or attention?

There will still be some publishers who continue to offer free access to their content online, but the amount and quality of that content will be limited. This will leave people inundated by content with little value, and will essentially dumb down the population who can’t afford to pay for better quality news.

The European Union was the first to reform its copyright policies, but it likely won’t be the last. And when these regulations take effect and spread throughout the world, what will average people do?

Earlier this year, Reuters predicted that reader revenue in the form of subscriptions will be the top priority for the majority of newspaper and magazine publishers in 2019 – a strategy that seems to conflict with other research reporting that the vast majority of people (including most students) are unwilling or unable to pay for digital news.

So under the EU’s new legislation, how will students get news that matters to them and their studies, when the highest quality content will be locked behind paywalls?

The trend towards more paywalls and internet regulation looks like a losing proposition for students. But all is not lost.

Quality aggregation is the future of news

Content aggregation has always been a part of our lives. Before the internet, newspaper and magazine publishers aggregated stories and advertising into papers and periodicals. Music labels aggregated songs into albums, and cable companies aggregated video content for people’s TVs. And of course, libraries have always aggregated all forms of content, for patrons to enjoy.

But then came the web, and with it the rise of platforms and newsfeeds that changed everything.

Paid content aggregators typically monetize news through subscriptions and sometimes advertising.

A small selection of these also support sponsored access models, which allow consumer-focused businesses (e.g. libraries, hotels, airlines, cruise ships, ferries and others) to pay up front and provide access to thousands of newspapers and magazines for their users.

Free content aggregators make money off of advertising, of course, and sometimes user profile data that they collect and sell to others – often without users’ explicit consent.

For users of these so-called ‘free’ platforms, the experience of reading the news can be frustrating. Most content is commodified, and that which isn’t is hidden behind paywalls. Worse still, many publishers offer an underwhelming user experience. Truth be told, most newspaper and magazine publishers have never been able to replicate the immersive reading experience on their websites that they’ve had for centuries in print.

And while I’ve written more times than I can count about how publishers need to evolve with the times in their transition to digital, there are a lot of good reasons why the layout and user interface of newspapers and magazines hasn’t changed all that much in 200+ years. It’s also why digital replicas of publications have remained a valuable transition vehicle for accessing printed content online.

Replica vs. website content: no contest

Digital replicas of newspapers and magazines retain the interest of readers longer than website content, for many reasons:

- A newspaper or magazine replica has a beginning and an end – a welcome reprieve from the glut of information we face daily online. When you finish reading an issue, you receive emotional and psychological benefits from the fact that you’ve completed something. You get a sense of closure – a sense of accomplishment.

- A replica of the print edition provides a more immersive reading experience, with the added benefit that it can be downloaded and read offline. Try that with a website.

- The traditional layout is familiar and consistent, not just within a single publication, but across almost all titles of a similar type. By contrast, there’s little or no consistency in media website design. They all differ in layout and style. Perhaps the only thing they share in common is an overabundance of friction points (e.g. paywalls, slow load times on mobile, popups, auto-play video, and other forms of distracting advertising).

- A replica’s user interface (typeface, headline size and style, article length, grammar, text spacing, white space, color usage, image size, and placement) is designed to provide visual cues to help people navigate the issue and discover relevant content. Readers gets an immediate sense of which stories are most important.

- Readers enjoy a higher degree of serendipity when reading a replica than when browsing a website. While reading an article in replica mode, our peripheral vision detects adjacent content, facilitating discovery of interesting information. But on websites, every article typically lives on its own page, isolated from all other stories. Once a person is finished reading an article, they’re often left with no alternative but to click back in their browser to look for something else to read – another unwelcome point of friction.

- Reading traditional media in replica form exercises both our linear (reading left to right or right to left, from start to finish) and non-linear (discontinuous) reading. Websites typically ignore linear reading preferences and instead facilitate non-linear reading through the overuse of hyperlinks, images, and video that encourage jumping from one piece of content or page to the next without ever finishing what was started. There’s a reason for that: it provides more opportunities to show you ads.

- Replicas are about breadth and depth of content, and contain “all the news that’s fit to print,” according to The New York Times’ slogan. Websites are more about volume, because volume means more pages, which means more opportunities for advertising revenue. But even amongst all those pages, you’d be hard pressed to find all of the content from the printed edition. Believe me, I’ve tried and come up woefully short.

- In the academic world of source-citing, replicas can be easily referenced because the content doesn’t change, unlike web content, where one article can evolve over time.

But digital replicas aren’t for everyone.

Traditional (often more mature) news consumers prefer to read digital replicas of publications thanks to their familiarity with the print product. But they, like their younger counterparts, also want enhanced features to make the reading experience more interactive. These can include things like instant translation, commenting, voice narration, sharing functionality, etc.

Digital natives often want more of a streaming experience that allows them to scroll through newspaper and magazine articles effortlessly on their mobile screens.

To serve these diverse audiences, aggregated news platforms must facilitate distribution and discovery of content in different formats. They must deliver the right content to the right person at the right time.

In content aggregation, curation is crucial

Algorithmic curation, done right, targets an audience of one – an important distinction in the era of “It’s all about me.” Because content that isn’t personal is likely not relevant. And if it’s not relevant, it’s not useful.

News consumers have also learned from other aggregators that you should never have to go searching for another piece of content. Take Spotify, for instance. Once a playlist, album, or song ends, Spotify will automatically play music which it ‘thinks’ you’ll like. And very often, its algorithm is right.

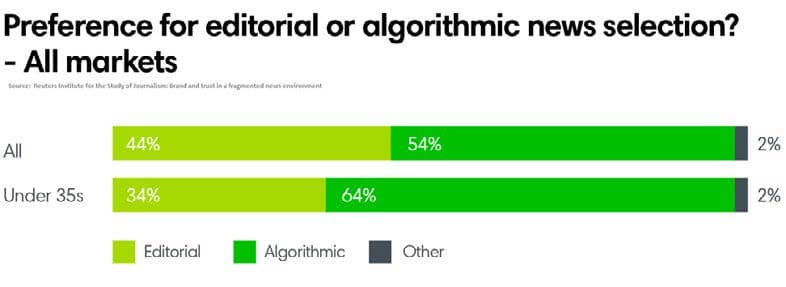

All content platforms, including news aggregators, use some form of machine learning to curate content for users – a strategy that is preferred by the majority of people, particularly the younger or tech-savvy ones.

People value the ‘independence of algorithms’ because they consider them to be less biased or swayed by editorial and political agendas. They also believe that algorithms help introduce them to a broader range of content and brands based on their interests and preferences, which are more topic-driven than bias-guided.

“It gets a variety of things – like I’m interested in certain topics that I probably wouldn’t find, or I’d have to search for it myself. So, it’s like a one stop shop of things that interest me.”

Focus group participant

‘Brand and trust in a fragmented news environment’ study

But as trusted as algorithmic curation is by many readers, it’s only as accurate as the data that drives it. If the data is inherently misinterpreted, incomplete, or manipulated (remember Facebook’s Trending Topics embarrassment?) the results can be anything from comical to catastrophic.

We’ve seen this far too often in the era of fake news, echo chambers, and duped readers who help spread misinformation and propaganda.

And then there’s bias. Whatever its form (political, economic, environmental, etc.), bias will always be a thing in the media world, even when you’re talking about the most trusted sources.

Sometimes the publisher is serving the interests of its owners by dictating what goes into an issue and what does not – something I’ve written about at length in The Insider magazine. Other times, it serves the interests of advertisers, who want to stage branded content as editorial.

And then there are publishers who are desperate to stand out in an ocean of content. By publishing deliberately biased content with clickbait headlines, they hope to attract more eyeballs and the ad dollars they trust will follow.

We can’t escape bias; it’s part of the human condition. This is why it’s important that readers not only enjoy a personalized reading experience based on their interests (e.g. topics, sources, columnists, etc.), but that they’re also exposed to multiple perspectives in the content they read, not just at the local or national levels, but at the global level too..

“While good journalism aims for objectivity, media bias is often unavoidable. When you can’t get the direct story, read coverage in multiple outlets which employ different reporters and interview different experts. Tuning in to various sources and noting the differences lets you put the pieces together for a more complete picture.”

Kevin Arms

Librarian and archivist

Lake-Sumter State College

Some aggregated news sites are algorithmically designed to share diverse global perspectives. Many platforms and publisher websites are not.

Librarians as pioneers and champions

The role of libraries and librarians in supporting our communities, enriching our schools, and sustaining our democracy cannot be overstated.

Their advocacy for equal access to content made them pioneers of the sharing economy when information was both scarce and highly valued.

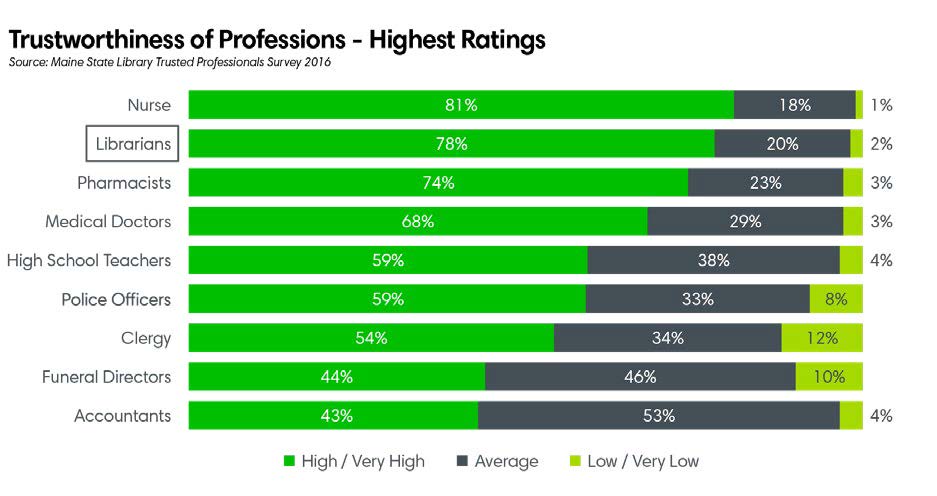

So, it’s no surprise that libraries rank highly among our most trusted institutions, with librarians being considered one of the most trustworthy professions.

Libraries as champions for local media

In almost every category of business, consolidation is inevitable, and the news industry is no exception. But instead of implementing smart consolidation to preserve the best journalism, what we’ve been seeing, especially in local media, is consolidation turned ugly. It’s happening almost on a monthly basis in North America and Europe. The common denominator throughout these consolidations has been an absent owner looking to capitalize on the struggles of the business.

By borrowing against the company’s assets, selling off unwanted properties, cutting newsroom staff, axing pension funds, and slashing other operational expenses, profit-driven proprietors are able to siphon off massive amounts of user data along with substantial profits from dividends, incentives, management fees, and tax breaks. Once the business has been exploited to the max, the owners who’ve made all their money back, either bankrupt it or sell it off.

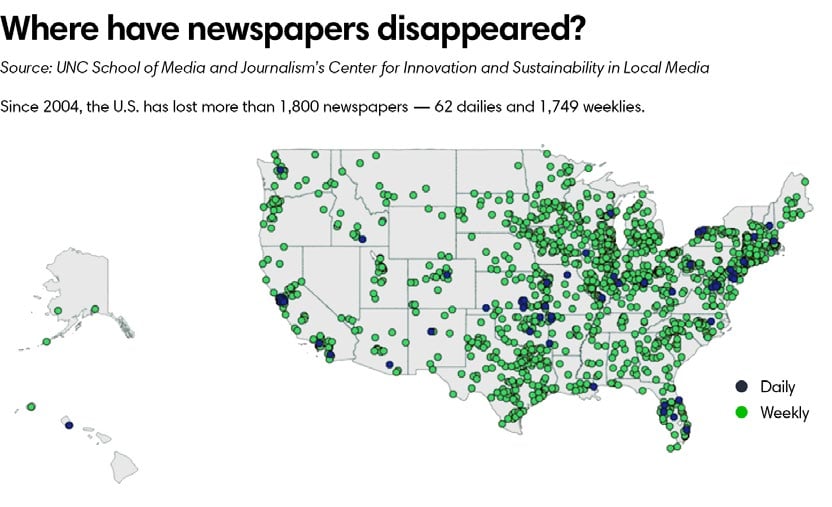

In the US alone, close to 20% (~1,800) of metro and community newspapers have either merged or gone out of business since 2004. And it’s far from over.

So, who’s stepping up to serve their communities and champion local journalism? You guessed it: librarians across the US and Canada are working hard (and often on their own time) to try and fill the void. But it’s a daunting task.

Librarians’ and educators’ roles in information literacy

“Students are hungry, we believe, for good models of engagement with news. They want to talk about news, both their frustrations and their longings for what they need from news providers. Accordingly, educators need to be more explicit about what a good “information diet” looks like, the drawbacks of being “always on,” and, most of all, what habits a discerning news consumer practices.”

Project information literacy: How students engage with news

To help empower today’s youth in its quest for information literacy, the PIL study offered up six recommendations for educators, librarians, journalists and social media platforms. Here’s a summary of those directed at specifically at librarians and educators:

- Integrate news discussions into the classroom.

- Help students learn more deliberately about the relevance of news.

- Consider a ‘writing across the curriculum’ program to help broaden student engagement with news, and encourage them to build connections between their news practices and their academic work.

- Help students understand the most effective way to vet and sort information.

Here are a few more I thought of:

- Make news literacy a mandatory subject in school, and offer it in public libraries as well. A survey of college students in 2017 found that “students who had taken a news literacy course had significantly higher levels of news media literacy, greater knowledge of current events, and higher motivation to consume news, compared with students who had not taken the course. The effect of taking the course did not diminish over time.”

- Help students learn where to spend their trust. Help them understand the risks of relying on social media and search engines for news sources.

- Open up the world of quality media to them, so they’re exposed to trusted news and information from around the world.

In the past, libraries offering printed media with a few select digital editions of periodicals and newspapers was sufficient to support the student body and teachers. At that time, Newspapers in Education programs adequately met a limited need for local and national news content. But today’s expectations far exceed these antiquated single-source solutions. The world of knowledge is at students’ fingertips, and they expect unlimited access to all it has to offer.

“I feel like with the world being so big, it’s just like we need a big platform to unite them all… We need a platform that anybody can hear about news.”

Male | 17

African-American

Source: How Youth Navigate the News Landscape | Knight Foundation

Moving forward

We all have a responsibility to be advocates for the truth, and suppressors of lies, hoaxes, ‘alternative facts,’ misinformation, and propaganda.

In 2019, let’s make a commitment to seek out and support quality journalism, and shun that which is not.

Let’s help those who struggle with information literacy by teaching them how to differentiate fact from fiction.

Because as Professor Brendan Nyhan from Dartmouth College once said, “standing up for facts is a kind of patriotic act, and a necessary one.”